I finished reading the book, Minka: My Farmhouse in Japan, on the same day that the US Supreme court finally overruled the infamous Korematsu vs US case, which epitomizes the injustice of the 1944 Japanese internment camps. Even without this relevant coincidence, I’ve been reflecting a lot about violence justified by “otherness” that’s happening in the states and around the world while I was reading this book.

Foreign policies are complicated and I don’t claim to understand the full scope, but for me, it’s immediately eye opening to view current events through a historical lens. It urges me to reflect on what we take for granted and accept as fate in our current times. In 50 years, what current events will we look on with the same bewilderment as we view the internment camps today?

It is with these emotions that I stumbled upon The New York Times short documentary on the aforementioned book. I sobbed deeply the entire way through. The book and the documentary capture the story of John Roderick, a correspondent and prominent “China watcher” who opened China to the west in the 50s. He found a home in rural Japan in a 300 year old Minka, resurrected by his talented adopted son, Yoshihiro Takishita, who then went on to dedicate his life’s work to preserving Minkas, a disappearing form of architecture.

Yes, it ticks off so many of my interests, such as architecture, Japanese culture and aesthetics, and Chinese history during that time, but more than anything, it is a heart-wrenching and triumphant story of two people who loved and built something together against all odds. I want to share the following prologue from the book as it captures the spirit of the story perfectly.

MINKA: MY FARMHOUSE IN JAPAN PROLOGUE:

“When the hurly-burly of today’s world overwhelm me with its news of the never-ending war between good and evil, love and hate, I hobnob with the rustic ghosts of centuries past in my restored old farmhouse on a hill, overlooking Kamakura, the ancient capital of Japan.

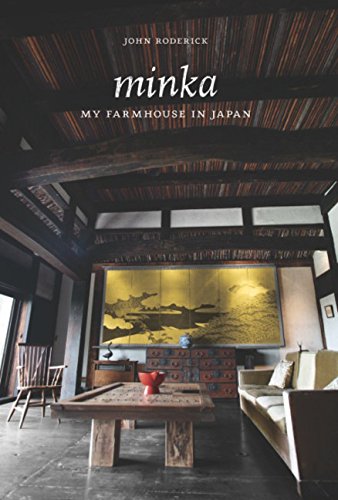

Its steep snow roof, massive posts and beams, wide wooden floors, and split-bamboo ceilings take me back 273 years to the tiny hamlet of rice farmers in the mountains where it was born, 350 miles from Kamakura.

The event on that distant day was a jubilant one because it was built for the village chief, Tsunetoshi Nomura, who doubled as its nature-worshipping Shinto priest. The place: Ise, in Fukui prefecture, 400 miles west of Tokyo. Its scattering of farmers all lived in such big farmhouses, called minkas, now a sadly disappearing type of building more than 2,000 years old.

I became the owner of this venerable pile forty-two years ago thanks to my surrogate Japanese family, the Takishitas (a name meaning “under the waterfall”) of Gifu prefecture. They took me, an American journalist and recent wartime enemy, under their wing in 1963, five years after I arrived in Tokyo to join the Associated Press staff there.

Actually, the minka was a gift from its owner, Tsunemori Nomura, the affable descedant of that long-ago ancestor for whom it was built. Parting with it was, for him, an almost unbearable sorrow. His ancestors, officers of a brave but doomed military clan called the Heike, had hidden, lived, ministered, and died in Ise since they had found refuge there following their twelfth-century defeat by Yorimoto, the first of Japan’s long line of military rulers, called shogun.

What followed was a labour of love. The Takishitas, joined by friends and family, dismantled, moved, and rebuilt the immense old house in Kamakura, where I lived. After defeating the Heike, Yorimoto made Kamakura—his military headquarters—the capital of a united Japan. The ghosts of the Ise Nomuras must have laughed bitterly to see their old home come to life again in the seat of their ancient enemy. Yoshihiro, the youngest Takishita son, a recent university graduate, supervised the entire project. It took forty days.

In my forty years as a foreign correspondent, I covered the Chinese civil war, the strife surrounding the creation Israel, and the French and American failures in Vietnam.

I spent seven months with the Chinese communist leader, Mao Tse-tung, in his 1940s cave capital of Yanan. And over the next thirty years, I chronicled the slow and sinister change in his personality from one of compassion for his fellow Chinese to blind hatred toward anyone blocking his dreams of personal power and conquest.

Turning from agrarian idealist to dictatorial tyrant, he publicly proclaimed that love was a bourgeois weakness, hate man’s most powerful emotion. Yet I cannot believe him; I am still convinced that in the end the meek will inherit the earth.

Searching for an example of the power of love, I have drawn on my own experience, the Takishita family’s gift of love and friendship whose living symbol is the old minka in which I still live.

It is a small example but it is significant because it happened in Japan, an implacable enemy that I—and so many Americans—once hated, intensely, blindly, and totally.

Often, in the eloquent silence of my high-ceilinged living room, I think I hear the voices of the Nomuras and their neighbors, chattering about the weather, the harvest, fishing, the hunt, the phases of the moon, and the religious mysteries of the deep forests.

It is then that the lovely old minka speaks to me of a time when nature and the rural sense of community sharing informed everyday life. Forty years after the Takishitas presented it to me, it is my private shelter from the global storms that rage all around us.

It represents, to me, the triumph of love over hate.

It is, at last, a house of my own.”